Thought for the week 💭

Could blockchains replace record labels?

[5-minute read]

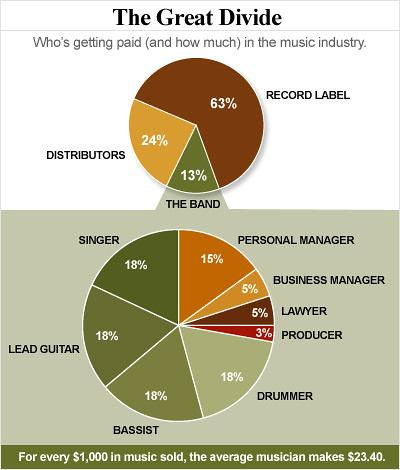

The 3 major labels (Universal, Sony and Warner) generated $1m per hour in music streaming revenues in 2020. In the same year, only 1% of artists on Spotify generated >$50k in annual streaming revenues. The remaining 99% generated less than this. What’s even more concerning is that of this $50k, the recording artist only keeps ~15% (<$7.5k) — with the labels, publishers and platforms taking the remainder.

This feels like a very broken system.

The key relationship in music is supposed to be between the artist and their fans. However, in reality, this is not the case. Intermediaries (labels and publishers) play a disproportionately high role and enjoy a disproportionately high proportion of industry revenues.

Historically, this made some sense. In a world without digital audio workstations (DAWs), high costs of CD & vinyl manufacturing and a fragmented network of retail distribution channels, labels were essential for music to exist. However, technology has changed this. Technology has made it considerably easier to produce, distribute and market music without the help of a record label.

Because of this, the proportion of unsigned artists releasing music without the help of a label increased to 6.3% in 2020 — a 28% increase vs. 2019.

I believe that this number will increase markedly over the coming years. What’s more, I believe that blockchain/Web3 will be essential in unlocking value for artists - helping to overcome the current plights of the music industry. Specifically, blockchains will disintermediate the music industry - shifting value away from the middlemen and into the hands of artists and their fans.

What do record labels do?

Record labels have three core functions:

1 — Funding

Arguably the most important function of a label is its role in providing artists with financing. Labels give artists access to capital so that they can produce and promote their music.

In this sense, labels are similar to VCs. A VC will give a company capital so that it can finance the building and marketing of its business. In exchange, the VC will receive an equity stake in the business. In the case of record labels, that ‘equity stake’ is usually 85% of all royalty payments from the song or album that is produced as part of the deal. Increasingly, due to a decline in royalty rates in recent years, labels also enforce 360 deals. These deals give the labels the right to a proportion (25-50%) of all revenues generated by that artist (e.g. from merch, concerts and sponsorships).

What is even more concerning about the current status quo is that the money provided by labels is a loan - not an equity investment. The artist must pay the label back for any financing that they have received out of their 15% royalty pool before they can pay themselves. This example may help explain a typical deal:

An artist signs a record deal for a future album with a label. The label gives them $500,000 in funding - which consists of an advance, and financing to cover the production and marketing costs.

The album then goes on to generate $2m in royalties. This is split as follows: 85% ($1.7m goes to the labels) leaving a $300k pool for the artist. However, the artist owes the label $500k to pay back the financing that they provided. As such, the artist is now $200k in debt to the label. This will be paid back via any merch or live performance sales (after the label has been paid their proportion of these revenue lines).

This is a very asymmetric value exchange.

2 — Distribution

In the days of physical music (CDs, tapes and vinyl), distribution was an integral role played the labels. Via their network of distributors - the labels were essential in getting music from its point of creation (recording studios) to where it could be heard and purchased by customers (retail stores).

However, in the current world of DAWs and streaming, the situation is drastically different. DIY distribution is now more feasible than ever before. Digital distribution is offered directly to artists via a number of digital-first distributors as well as directly via many of the streaming platforms. Chance the Rapper made history in 2017 when he became the first musician to win a Grammy without signing a record deal or selling any physical copies of his music. As such, this function is rapidly losing relevance.

3 — Marketing and promotion

This is the most intangible - yet arguably the most persistent value-add of record labels. Labels offer artists exposure on an international scale. They can provide connections to top publicists as well as other key stakeholders in the broadcasting and media world. Through their network, they can get artists added to Spotify playlists, or help them strike interesting partnership and licensing deals. This comes from the power of the labels’ network.

What are the problems with the current system?

1 — Lack of access

Only 1/42 artists who submitted demos to the 35 biggest labels in 2020 successfully secured a deal. More concerningly, only 10% of those who get signed a deal end up getting their music released (due to artists frequently getting ‘dropped’). The current system has major barriers to entry for most artists.

2 — Artist economics

According to TheRoot, for every $1000 in music sold, the average contracted recording artist takes home about $23.40. That equates to 2.34% of gross revenues. This has resulted in a situation in which 80% of music creators earn less than £200 a year from streaming. (!!!!????!!!!)

3 — Lack of creative freedom

The terms in many label deals can be stringent. For example, the labels will often have a say in what expenses are necessary for the creation of an album. An artist will have an incentive to keep costs down since they are the ones who will bear brunt of paying these costs back. However, the labels still have the final say in what is necessary.

Meanwhile, in many cases, the labels will have a strong role in influencing the creative direction of the artist’s music. Stringent, multi-year contracts leave little wiggle room for the artist to experiment and change direction. This has resulted in several blockbuster court cases.

How could blockchains be substituted for record labels?

In my view, blockchains can be used to replace the three core tasks of a record label (funding, distribution and marketing/promotion).

Funding

Smart contracts can be created that enable artists to sell the music rights to their songs/albums to fans, speculators or even labels. The terms of these contracts are immutable - and do not rely on any centralised party to exist. This puts the power in the hands of the artist - who now benefit from being able to set their own licensing terms.

Instead of relying solely on the will of a handful of labels, they would operate under free-market dynamics based on supply and demand. If the artist has a sufficient base of interested parties willing to invest in or support their music - they will benefit from more attractive terms than in the current system. For example, instead of an artist borrowing $500k from 1 record label to produce their next album in exchange for 85% of their royalties, they can ‘crowdsource’ this from 100 (or 1,000 or 10,000) of their biggest fans in exchange for a 25-50% royalty revenue share.

Fans benefit from passive income and from supporting their favourite artists, while artists benefit from more favourable terms and lower revenue share rates. In this way, Web3 instruments provide artists with a wider pool of capital as well as a deeper connection with their fans.

We have already seen early examples of this. For example, earlier this year Jacques Greene sold the rights to his upcoming album Promise as an NFT on Foundation. Other artists have also done this, including Big Zuu and Taylor Bennett.

Distribution

In the digital age, distribution has already been solved by existing technologies. However, blockchains can help in solving two of the biggest existing sub-issues in digital distribution - namely i) attribution and ii) payments.

It is estimated that ’several’ billions in revenue is lost every year due to a failure to correctly attribute the music to the relevant rights holders. The problem is simply that no central database exists to keep track of information about music. The required metadata exists in thousands of different sources with no single point of authority. Consolidating this and extracting a single source of truth is an arduous (and arguably impossible) task.

Blockchains provide an elegant solution to this problem. A music blockchain would be a single place to publish all information about who made what song, without having to trust a third-party organization. Companies like Mediachain are already addressing the problem of music attribution using blockchains.

There are also interesting potential wins to be made on the payments side — with blockchains enabling instant micropayments instead of requiring artists to wait 6+ months to receive royalty payments as is currently the case.

Marketing and promotion

This is arguably the hardest of the labels’ tasks to disrupt using any technology. However, I believe blockchains can address this indirectly. Specifically, if an artist is ‘raising’ money from a few thousand people as discussed above — they now have a stream of ambassadors - financially incentivised to push this artist and help them in growing their career.

What’s more, these fans don’t necessarily have to be your typical stan (music superfan). Instead, they could feasibly be speculators or independent A&R professionals who have existing networks that they can leverage to support the artist. I believe in this way, blockchains could disintermediate A&R professionals in the way Web2 technologies did for other professions (e.g. Fiverr → graphic designers, Upwork → developers). I believe that blockchains could usher in the age of the freelance/independent A&R professional and/or music investor.

Concluding thoughts

Web3 technology gives artists the power to build their own economy. I firmly believe that blockchains will enable the disintermediation of the music industry — allowing artists to independently fundraise, create and distribute their work in the way that they choose. This will lead to a growth in ‘the music entrepreneur’ - and a rise in the number of independent music professionals who invest and work directly with musicians. I believe that this is the path to a more sustainable music economy.